Alphabet Soup

One of the nicest things about Zope is its ability to separate an application’s presentation layer from the business logic that drives it. It does this using its very own tag-based markup language, Document Template Markup Language or DTML.

What’s DTML? Well, as the Zope Documentation Project at http://www.zope.org/Documentation/Guides/DTML-HTML/DTML.3.html puts it, it is “…a facility for generating textual information using a template document and application information stored in Zope. It is used in Zope primarily to generate Hypertext Markup Language (HTML) files, but it can also be used to create other types of textual information.” Or, to put it in words you and I understand, DTML is HTML on steroids.

I don’t say this lightly. After all, HTML is fairly popular by itself - it’s the language used to mark up every Web page on the planet, and required study for any Web developer. But DTML is much more than plain-vanilla HTML - it’s a proper programming language which comes with variables, loops and decision making constructs, together with string and math functions borrowed from Python. It’s also fairly easy to use - as you’ll see over the next few pages.

Before I begin, though, make sure that you have a working copy of Zope (this tutorial uses Zope 2.5.0), and can log into the Zope management interface. In case you can’t, drop by http://www.zope.org/, get yourself set up and come back when you’re ready to roll.

Upper Management

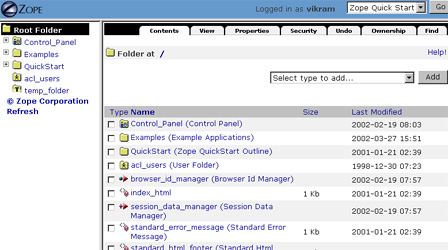

Once you’ve got Zope all set up, start it up and log in to the Zope management interface with the user name and password that was created when you installed Zope. You should see something like this:

This is the tool that you will be using to build your Web applications. You can use it to create documents, folders, and your own Zope products. And the first step in this process is to create a folder to store all the methods and objects that I’m going to be constructing.

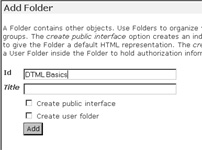

Select a Folder from the drop-down menu that appears at the top of the page,

and give it the ID “DTML Basics”.

You don’t need to create a public interface at this time.

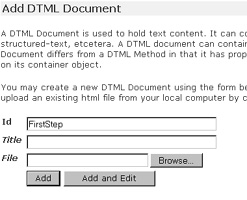

The next step is to navigate to the folder that you just created and add a DTML Document object to it, using the process outlined above. Give this document an ID of “FirstStep”.

As you may have guessed by now, the object ID that you assign at each stage is fairly important - it provides a unique identifier for the object within Zope, and can be used to access and manipulate it from your DTML code.

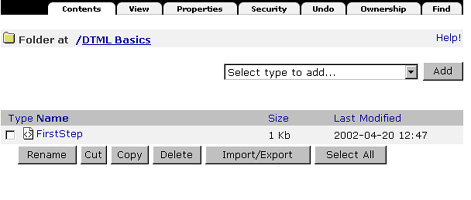

Once you’ve assigned the document an ID and saved your changes, you will be returned to the main folder listing. Your newly-minted object should now show up in this listing.

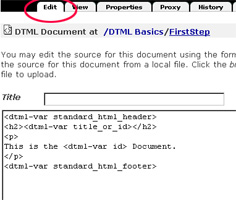

Right. Now, how about editing it? Click the “Edit” menu function (look at the tabs at the top of your screen) and Zope will show you a form containing the current contents of the FirstStep object instance.

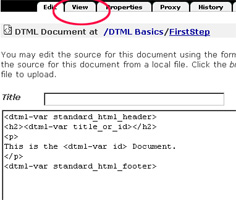

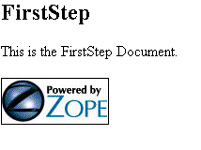

In case you’re wondering, the strange mishmash of characters on your screen is raw DTML. Don’t worry too much about what it all means - I’ll explain it shortly - but instead, focus on what it does. Click the “View” tab at the top of your screen

and take a look at the output of all that code.

Pretty cool, huh?

Dissecting DTML

Let’s take a closer look at the DTML code which generated the screen on the previous page.

<dtml-var standard_html_header>

<h2><dtml-var title_or_id></h2>

<p>

This is the <dtml-var id> Document.

</p>

<dtml-var standard_html_footer>

As you can see, this code block contains both HTML and DTML. When Zope processes this DTML Document instance, the DTML tags within it will be processed, and will be replaced with the resulting output. If you’re familiar with PHP, JSP or ASP, this tag-based approach should already be familiar to you.

The first line of code

<dtml-var standard_html_header>

merely inserts the value of the DTML variable named “standard_html_header”. This is one of the few predefined variables available in Zope, and, as the name suggests, it is used to display a common header for your site.

Next, the lines

<h2><dtml-var title_or_id></h2>

<p>

This is the <dtml-var id> Document.

</p>

fetch and display either the document’s title or its ID. If no title is available (as is the case here, since I never specified one when I created the object), Zope will make do with the ID.

Finally, the line

<dtml-var standard_html_footer>

inserts the value of another predefined Zope variable, “standard_html_footer”. No prizes for guessing what this one’s used for!

Obviously, you can just as easily omit all the DTML code and use a static HTML document - like this one:

<html>

<head>

<basefont face="Arial">

</head>

<body>

<h2>Can you say dee tee em el?</h2>

</body>

</html>

Zope will look for DTML tags within it and, finding none, will simply render the HTML as is.

Of Methods And Madness

In addition to DTML Documents, Zope also includes a strange animal called a DTML Method. There are a number of fairly obvious similarities between a DTML Document and a DTML Method, together with some very subtle differences. It’s the differences that can catch you out - which is why you should get to know them at this stage itself.

The most important of these differences is that while a DTML Document is an object with properties of its own, a DTML Method is an object which inherits properties from its container. Which is why, if you create a DTML Method

and take a look at it in the Zope management interface, you’ll notice the absence of a “Properties” tab on the top of the page (DTML Documents, on the other hand, have a very visible “Properties” tab).

As an illustration, create two objects, one a DTML Document and the other a DTML Method, and attach the following code to each:

I am <dtml-var id>

Now, when you view these objects, you’ll see that the DTML Document displays its ID correctly,

I am FirstStep

whereas the DTML Method displays the ID of its container - the parent folder (which I named “DTML Basics” a couple of pages ago).

I am DTML Basics

Consequently, DTML Documents are typically used to display static content, while DTML Methods are used to display dynamic content..

More information on the distinction between DTML Documents and Methods can be found at http://www.Zope.org/Members/michel/HowTos/DTMLMethodsandDocsHowTo

Introducing Yourself

Let’s move on to variables, the lifeblood of any programming language. DTML has them too - although, if you’re used to the way variables work in other languages, DTML’s interpretation can take some getting used to. More on that later - first, a simple example:

Hello. My name is <dtml-var myName>.

This code belongs to a DTML Document with the ID “Introduction”. The <dtml-var> tag is used to insert the contents of a DTML variable - which, over here, is called “myName”.

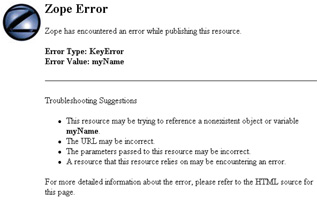

Here’s what Zope says when I attempt to view this Document:

Why the barf? Because despite Zope’s best efforts, it coldn’t find a variable named “myName” anywhere - and so it had to generate the error above.

You can make the error go away with one minor addition to the code above - add a default value for the variable via the “missing” attribute, and Zope will be happy.

Hello. My name is <dtml-var myName missing="Neo">.

And this time, when you attempt to execute the DTML, here’s what you’ll see:

Obviously, you can’t define values for variables in this manner for very long - it tends to negate the point of having a variable in the first place. And so, Zope comes with something very cool - the ability to automatically inherit, or “acquire”, variable from the Zope namespace. This capability to automatically search for and acquire variables is one of the most interesting things about Zope - and also one of the most common pitfalls for newbies.

In order to obtain the value of a named variable, Zope will first look in the current folder, and then recursively iterate through the folders above the current folder until it finds the named variable. In the event that it doesn’t, it will check a couple of other places (most notably the REQUEST namespace that is created when a form is submitted) and - if it still doesn’t find the variable - die with the error message above.

Acquisition in the Zope framework is fairly important, and so fundamental that you’ve already encountered it once before in this tutorial (although, obviously, you didn’t know it). Flip back a couple pages, and look at that first example, and its output again:

<dtml-var standard_html_header>

<h2><dtml-var title_or_id></h2>

<p>

This is the <dtml-var id> Document.

</p>

<dtml-var standard_html_footer>

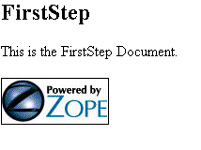

Here’s the output:

Wondering how that Zope logo got into the final output? Well, that’s acquisition at work. You see, when Zope is first installed, it automagically creates a couple of objects in the root folder. They’re named “standard_html_header” and “standard_html_footer” respectively, and - if you peek into them - you’ll see that they contain the following code:

<!-- contents of standard_html_header -->

<html><head><title><dtml-var title_or_id></title></head><body bgcolor="#FFFFFF">

<!-- contents of standard_html_footer -->

<p><dtml-var ZopeAttributionButton></p></body></html>

Pay attention to the footer there - you’ll see that it contains a reference to a Zope variable named “ZopeAttributionButton”. This variable actually references the Zope logo; this logo gets attached to the bottom of every page that uses this standard footer.

What does this have to do with acquisition? When Zope finds a reference to “standard_dtml_footer”, it searches through the folder hierarchy until it finds, or acquires, an object with that ID, and replaces the variable placeholder with the contents of that object. So, even though I’ve not defined those two variables in the folder containing the FirstStep object instance, Zope still possesses the intelligence to find them and use them within the DTML script.

In case you’re interested, you can read more about acquisition at http://www.Zope.org/Members/Amos/WhatIsAcquisition

Green Cheese And Pink Frogs

You can also format variable values with DTML’s numerous formatting attributes. Consider the following DTML Document, which contains a simple HTML form.

<html>

<head></head>

<body>

<form action="FormatForm" method="post">

<input type="hidden" name="someString" value="the cow jumped over a hunk of green cheese, and a pink frog turned into a hummingbird">

<input type="submit" name="submit" value="Hit Me!">

</form>

</body>

</html>

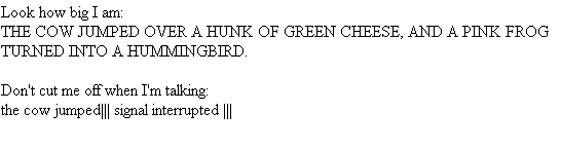

Once this form is submitted (to another DTML Document instance named “FormatForm”), the form variables and their values become available within the Zope namespace. Here’s what FormatForm looks like:

<html>

<head></head>

<body>

Look how big I am:

<br>

<dtml-var someString upper>.

<p>

Don't cut me off when I'm talking:

<br>

<dtml-var someString size="14" etc="...">

<p>

</body>

</html>

It isn’t very hard to guess what this script does:

The <dtml-var> tag comes with a bunch of attributes designed to format the data within it. Here are the important ones:

capitalize - uppercases the first character of the variable;

upper - uppercases the entire variable;

lower - lowercases the variable;

size - restricts the number of characters of the variable that are displayed;

etc - displays a string following the variable.

You can also format the display of the DTML variables using “structured text”, which, according to http://www.Zope.org/Members/millejoh/structuredText, is “…text that uses indentation and simple symbology to indicate the structure of a document”. Or, in other words, structured text is a set of predefined rules that Zope understands and can use to automatically format your document for you.

In order to see how this works, add the following line of code to the form above,

<input type="hidden" name="someOtherString" value='"Liked this? Send me mail", mailto:[email protected]'>

and the following line to the form processor:

<dtml-var someOtherString fmt="structured-text">

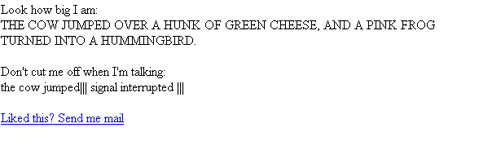

Here’s what the revised output looks like:

As you can see, Zope uses its structured text rulesets to automatically hyperlink the text string to the email address specified.

I’m not going to get into the details of structured text here - there are some great references out there, with my personal favourite being the one at http://www.zope.org/Members/redsea/Wiki/StructuredTextRules. Play with it, and you’ll get the hang of it soon enough.

In the meanwhile, I’m out of here. But fear not - your journey into the wild and wacky world that is DTML has just begun, and I will be back with more next week, complete with maps and lollipops. See you then!

Note: All examples in this article have been tested on Linux/i586 with Zope 2.5.0. Examples are illustrative only, and are not meant for a production environment. Melonfire provides no warranties or support for the source code described in this article. YMMV!

This article was first published on 06 May 2002.